Can you be homesick for a place that many would argue isn’t even really your home? My answer is unequivocally yes. I had my first day of college classes yesterday, and had Arabic at the ungodly time of 8:10-9:50pm. Needless to say, I was already feeling rather tired by the time it was over, but when the teacher played a video with photos of various Arabic-speaking countries and Oman came on the screen, the emotions I haven’t really felt all week came down upon me all at once. I have only cried in class once before, during a particularly horrific maths class in Oman in which a test was returned to us and I found out that I had scored 33%, but I can now say that I have cried twice in class. The combination of patriotic music with beautiful photos of some of my most beloved areas of the country I have come to love as my own hit me with a profound feeling of nostalgia and, well, homesickness. I miss Oman- the vibrant culture, the welcoming people, the breathtaking beauty, the unique pace of life- more than I had anticipated. As I remarked to my parents, who I called up crying- they were rather taken aback when I told them that I was homesick not for Nantucket, but for Oman- I guess this is what you get for going abroad. No one is exaggerating when they tell you that going abroad means that you will never be entirely at home again. I left part of myself in Oman; there’s a little piece of my heart in Ghala, in Wadi Adai, in Salalah, in Nizwa, in Muttrah. Oman is just as much my home as Nantucket is and as American University will become, and there’s nothing wrong with being homesick, regardless of which home it is for.

Two Years Later, Or What They Can’t Tell You At PDO

To say that returning to the 4H Center to act as YES Abroad’s Oman alum for the Pre-Departure Orientation was strange would be an understatement. To say that it was unnerving and bizarre would be more accurate, but would still fail to accurately portray the mix of nostalgia and deja vu I experienced that weekend. A little more than two years ago I was there for my PDO, exhilarated, nervous, and (not that I knew it then) incredibly naive. I remember agonizing over my impending departure, unaware that the questions which felt important then, like what shoes to bring to wear with my school uniform, would quickly pale in comparison to the new challenges and excitement which came with living in a new country. I remember being overly excited, bordering on giddy, with my fellow YES Abroad Oman 2013-2014 girls. I remember making memories which I laugh at to this day- “I’m yallah-ing!” I remember the legendary soft-serve, which is as good as everyone makes it out to be. I remember feeling apprehensive about meeting my group, and wondering how our relationships with each other and dynamic as a group would transform over the next ten months. I remember the group activities we did, some cheesier than others, and some which reappeared at this year’s PDO (I’m looking at you, blue and yellow sunglasses). I remember hearing for the first time the words that haunt me to this day: “not good, not bad, just different”. More than anything, though, I remember realizing for the first time that I really was going abroad, for ten months, to a country over seven thousand miles away, where people spoke a different language, wore different clothing, practiced a different religion, and were (in my mind) as different from me as one could be. While I later learned that many of my assumptions were unfounded (the vast majority of Omanis speak at least some English, many wear jeans on a daily basis, and most listen to American pop music), this anticipation of being different was intimidating. Innocent little white, blonde, blue-eyed me, who had never left the United States before and rarely left the 47.8 square mile spit of sand she called home, was about to become a minority for the first time. How would people view me? Would they resent me or in some way hold me accountable for the fact that my country’s tendency to interfere in issues in the Middle East had in part led to the increased destabilization of the region? The answer was no, by the way. Omanis are very good at separating the government’s actions from the way they view the country’s citizens, something we Americans should learn from. Would they welcome me, or would they always see me as different? The months that followed my PDO leading up to my departure were filled with days at the beach, shopping for suitcases and culturally-appropriate clothing, and plenty of emotions. I would be sitting at the beach, or on my sofa, and begin crying for no reason other than I knew that my life which had been so predictable and formulaic up until that point was about to change drastically. It wasn’t sadness as much as trepidation; I was excited, of course, but I wasn’t sure what I had gotten myself into. I had focused so hard on getting the acceptance email that I had all but forgotten about the fact that this email was only the beginning. I was afraid, not because I was going to the Middle East, a region people tend to fear, but because I was leaving home. How would I cope? Would I enjoy my experience? Would I feel satisfied at the end of the year, or would I regret my decision to go abroad? I didn’t know, and this terrified me. I was used to living in my four-member family, attending my high school, and living out my days in predictable patters- I was not used to leaving all I found to be normal and embarking on a journey which was simultaneously thrilling and incredibly intimidating.

Despite my worries, I stepped on the plane in August, and as the year proceeded, what was once strange and different became normal, and I began to feel as comfortable in Oman as I had back on Nantucket. I felt as much a part of 3yn Ghala and Azzan bin Qais as I was a part of Nantucket and Nantucket High School. I felt as much the granddaughter of Abdullah, Noora, Omar, and Shamsa as I was the granddaughter of Frank, Rose, Jane, and Bruce. My school, friends, family, and community in Oman didn’t replace their American counterparts, but they too became a part of who I am. They tell you at PDO that exchange is more than just a year of your life, and that you can’t “un-become an exchange student”, but they can’t begin to get across to you the extent to which exchange will permeate every facet of your being. You will return the same person you were when you left, but enhanced in ways unimaginable to you now. When my fellow alums and I spoke about the questions our groups were asking us, we agreed that there are things we simply cannot explain to them. When we gave them a response which seemed weak at best, we were not trying to avoid answering the question; we simply couldn’t. Some questions require answers too complex or too personal to be comprehended by someone who has not gone on an exchange. Some things have to be felt to be understood. This is something which became clear to me through my participation at this year’s PDO. When one alum said something on a panel, more often than not the rest of us would begin nodding in agreement. While our countries are each unique and every exchange is different (to everyone in this year’s PDO, I’m sorry for saying this yet again), some experiences are truly universal. Exchange students can relate to one another in a way different from any other I can think of.

Through participating in an exchange program, you will create a bond with exchange students you don’t even know exist. You will learn to appreciate and learn from the world in a way completely foreign to you. You will no longer be able to feel at home in any one place. You will learn what you are capable of, and become more self-reliant and self-assured than ever before; the challenges will make you stronger. You will emerge from this experience an improved version of yourself. We can say all this, but you won’t understand until you have experienced it for yourself. Get out there and make the most of your year. Take risks (responsibly), laugh at yourself, go on adventures, stumble your way through a new culture and language, take initiative, make mistakes, push yourself out of your comfort zone, and fall in love with people and places thousands of miles away. Believe me when I say that you will thank yourself for it.

Villanelle about Niqab

For AP Literature, I was asked to write a villanelle (a type of poem) about any subject I wanted. I decided to write about the niqab and abaya, the full-covering some Muslim women chose to wear. In recent years, the niqab has become a politically-charged item of clothing, and has been banned or challenged in multiple countries around the world. Currently, the Netherlands are moving forward with a partial ban of the niqab.

The niqab. For a description of the different types of covering, visit this blog post.

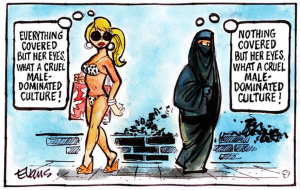

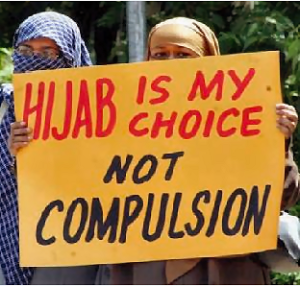

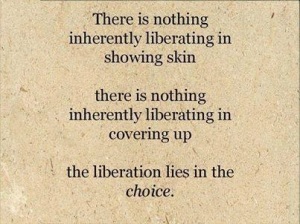

In France, the main argument for banning the niqab was that some women may be forced to wear the niqab, and banning it would liberate these women. After hearing this, millions of people, both Muslim and non-Muslim, wondered, what about the women who chose to wear it, often against their family’s wishes? Wouldn’t barring someone from wearing the niqab be just as opressive as forcing someone to wear it? Clearly, on both sides there are strong feelings, as exemplified through this CNN interview.

Many women see niqab, hijab, etc. as a form of rebellion and a way to refuse to be judged based on their looks. Image courtesy of Google.

One of my personal pet peeves is when people insist that all women who cover themselves with a hijab, niqab, abaya, etc. are somehow forced into doing it. While there are no official numbers as to how many women wear the niqab worldwide, the vast majority do it on their own accord. In this CNN podcast, American niqabi Nadia explains why she wears the niqab. She believes that it is not a practice madated by Islam, but rather that it brings her closer to God and forces others to judge her solely on her intellect as opposed to her looks.

Niqab, hijab, abaya, jilbab, etc. are all issues which people feel very strongly about, but instead of outlawing this or mandating that, why don’t we allow women to chose for themselve what to wear? After all, isn’t that true liberation?

Villanelle about Niqab

I have never before felt so free as a woman,

though some may believe these yards of fabric imprison me.

I refuse to be the plaything of men.

The temptations of this world I abandon;

The beautiful lies of advertisements don’t beguile me.

I have never before felt so free as a woman.

Walking in the city, I am unknown, unharassed by men.

When I pass them, they lower their gazes away from me.

I refuse to be the plaything of men.

I see her beside me, her speckled-with-goosebumps skin,

her head held too high in a vain attempt to be confident- she contrasts so much with me.

I have never before felt so free as a woman.

No longer must I expose myself, nor show my chin,

Nor my nose, nor my lips, nor my face- indeed, none of me.

I refuse to be the plaything of men.

I notice her as if I am staring in a mirror- I see her, my twin.

A woman who is covered like me. Both she and

I have never felt so free as women. Both she and

I refuse to be the plaything of men.

Interview

Here is an interview I did recently with the local TV station regarding my time abroad.

License Plates

I recently found this post lost in the vaults of my drafts, so here it is, a bit late!

——

My brother recently asked me to send him a picture of an Omani license plate. I felt a bit like a private investigator doing so, but I did. Omani license plates are very much a status symbol. In Muhammad’s bus on our way to the AMIDEAST center, it is not uncommon for us to be in the middle of a conversation and have someone yell out, “4444!” Because us YES Abroad-ers aren’t particularly fond of math, these numbers tend to refer to license plates rather than anything else.

As I said earlier, license plates are a status symbol. The “good” numbers (with either few numbers or repeated numbers) can be extremely expensive. Omanis will even pay up to 10,000 OMR for a “good” plate number, which converts to roughly $25,000. Numbers such as “1” are often the mark of governmental vehicles. We often joke when we see a 1, “Oh, there goes the Sultan on a little drive.” And who knows? Maybe we’re right.

When it comes to license plates in Omani, the “better” the plate, the fewer the numbers. So in actuality, Omanis who pay incredible sums of money for “good” plates are paying to have fewer numbers on that plate. The normal run-of-the-mill plate will have either four or five digits, as well as a few letters. As the plates get better and better, and the price tag gets bigger and bigger, the number of letters and numbers reduce.

Unitarian Church Presentation

I’ve been back on Nantucket for a little more than two months now, and am looking foreword to giving my first presentation about my time abroad! I will be speaking at the Unitarian Church on September 7th beginning at 10:45am, and I’ll be available for questions at the coffee social following the service. I’ll be talking about Islam and my daily life in Oman, among other topics. The service is open to anyone who wishes to come, so please come if you can!

This is the essay which accompanied my capstone project, a final project we are required to do for YES Abroad. I modeled mine after Humans of New York.

——–

Even before I came to Oman, I knew that some Americans have large misconceptions regarding Arabs, Muslims, and the Middle East. While some of these stem from ignorance and a lack of cross-cultural dialogue, more often than not the root of this problem is the media. In our modern world, the media is a part of our daily lives, often in ways so subtle that we do not even realize it. Our perceptions of our world and the people we share it with are influenced, and sometimes tainted, by what we see on the news or in the magazines. The ways we interact with people who are different than us are changed by the stereotypes we hold to be true. Why are the stories that promote these prejudices so prevalent?

The media is not only committed to distributing the news. It is easy to forget that behind every news channel, magazine, radio station, or newspaper is a company whose ultimate goal is to make money. How do they do this? By finding exciting stories that give us what we want. If a television program or magazine doesn’t interest us, we will switch away from the channel or begin to buy a different, more exciting magazine. Though obviously the media cannot spout pure lies for the sake of making money, it can manipulate facts in a way to make real events more interesting to the general public. There are three major themes that draw us in and capture our attention: violence, horror, and mystery. By packing their stories with these topics, companies are able to create a stable base of consumers and maintain a constant flow of money. However, if we manage to tear our eyes off the television and go out into the world, we will be faced with a far more benign world than the one we expect. In our everyday lives, most of us are not faced with extreme amounts of violence, horror, or mystery. It is not entirely fair to blame the various industries which make up our media for the disparages found between the real world and the world we find on the screen of a television or the pages of a newspaper; a lot of what the media is feeding us is a reflection of what we want. This is why we often see a negative view of Muslims, Arabs, and the Middle East whenever we switch on the television; the people reporting on these stories know that if they inject violence, horror, an air of mystery, or an “us vs. them” feeling into their coverage, more people will watch it. Unfortunately, the amount of emphasis placed on the individuals on the very outskirts of society who do commit grievous crimes can often blind people to ever thinking of the normal, everyday people who go about their lives in a very similar way to everyone else.

In the case of Muslims, when a person commits a crime and happens to be Muslim, a surprising amount of emphasis is placed on their religion. However, if a Christian were to commit the same crime, they likely would not be labeled a “Christian extremist”. As an effect, people begin to think that all Muslims are like those they see on the news, and some people go so far as to label every Muslim a terrorist. Contrary to what many believe, Islam is not a religion that preaches hate, terrorism, or oppression.

I sometimes find it hard to believe that people do sincerely and honestly consider the Middle East, where I live, to be unwelcoming and full of hostile people. The Omanis I know, all of whom are Muslim, are some of the nicest, most hospitable people I have ever met. I have never felt unwanted or uncared for during my time here. Where were the stereotypical oppressed women clad all in black who never leave the house? The religious zealots who shun me for not being Muslim? They simply don’t exist in my daily life.

As I began to realize how different the stereotype of the Middle East is from the day-to-day reality of this area, I started to think of what I could do to help rectify this misunderstanding. I think the problem is that Americans are rarely exposed to stories which highlight the kindness of Arabs and Muslims. The extremists are all they see in the media, and their view of the Middle East and Islam is tainted as a result. I think that many of our prejudices stem from the belief that certain groups of people are different from us- the “us vs. them” mentality. However, what we don’t realize is that we are all humans. In the end, we all share similar values and goals. If people could realize this, they would be able to forge an understanding between themselves and people of a different race, ethnicity, religion, or way of life. It is important to focus on the similarities rather than differences. By sharing the stories of ordinary people who live here in Oman, I am trying to present a less skewed version of the Middle East to people who may never get the chance to travel here. By showing normal men and women going about their daily lives in a peaceful manner, I am hoping to abolish some of the stereotypes people may have. Yes, we may dress differently and speak a different language, but at the end of the day, we are far more similar than we are different.

Women And Islam, Part 3

Mothers’ Day is rapidly approaching back home in America, though the holiday has already passed here. In Islam, mothering is one of the noblest tasks. One of the most convincing examples of the high status women are given in Islam is the exalted position of mothers, as outlined in the Qur’an and hadith. Heavy emphasis is placed on the work mothers do, and all people are commanded to obey, respect, and care for their parents.

In the Qur’an, servitude to one’s parents is mentioned directly after servitude to God. “Worship God and join not any partners with Him; and be kind to your parents…” (Quran 4:36). While the former is obviously the most important, the Qur’an does not overlook the duties one has to one’s parents.

The following verse addresses the many challenges faced by parents, and puts additional emphasis on the work of the mother, as she faces tasks a father doesn’t. “And We have enjoined upon man, to his parents, good treatment. His mother carried him with hardship and gave birth to him with hardship, and his gestation and weaning [period] is thirty months. [He grows] until, when he reaches maturity and reaches [the age of] forty years, he says, ‘My Lord, enable me to be grateful for Your favor which You have bestowed upon me and upon my parents and to work righteousness of which You will approve and make righteous for me my offspring. Indeed, I have repented to You, and indeed, I am of the Muslims.’”

The debt owed to our parents can never be fully repaid. Think about all the discomfort mothers endure while pregnant, and the hardship of labor, the nights spent up with crying or sick children and the hours of worrying about them and their future. However, this doesn’t mean that we should take them for granted; rather, we should be grateful to them and try our best to make their lives happy and to ease their difficulties.

Each Muslim has many duties towards his or her parents, the most important of which are outlined in the following passage: “To be kind to one’s parents is: to obey them when they order you to do something, unless it is something which Allah has forbidden; to give priority to their orders over voluntary acts of worship; to abstain from that which they forbid you to do; to provide for them; to serve them; to approach them with gentle humility and mercy; not to raise your voice in front of them; nor to fix your glance on them; nor to call them by their names; and to be patient with them.” The work of a parent is never done; parents never stop loving or worrying about their children, no matter how old they are. If our parents endured so much for us, shouldn’t we at least try to compensate them for what they have done?

I’ve been in Oman now for a little over eight months. While saying that seems incredible, living here now feels common. As my time here comes to a close, I am having trouble imagining living in the US once again. The fears I had when I embarked to Oman are very similar to the feelings I have now, as I am about to return to home. But is it home? An old saying claims “home is where the heart is”. Well, right now Oman is home. Oman is where I have found myself, where I have tapped into resources of strength I didn’t know I had, where I have navigated souqs with my limited Arabic and where I have learned more than I can put into words, both about myself and about the world around me. This is home.

When I received my acceptance letter to YES Abroad after a day of anxiously refreshing my email, a million thoughts tumbled through my head. I thought that I would learn so much about Middle Eastern culture, about Islam, and about Arabic. While I certainly have learned a lot about these topics and others, I never could have imagined the real span of learning that would take place here.

When I left Nantucket, I had to switch off my emotions in order to even get on the plane. I remember that I wrote the following right after I arrived in Oman: “I began travelling on August 24 at 8:32 in the morning with a flight to Providence, RI. The night before I left was very difficult; I didn’t get much sleep and, frankly, I was an emotional mess. It was so overwhelming to think that the time had come for me to actually leave my home, my family, and everything I knew for an entire nine months. Once I arrived at the airport, some of my excitement returned. Nonetheless, hugging my family goodbye was the hardest thing I have ever done.”

Soon I have to return home. Though I love Oman, I am excited. I will once again be able to see my family. It feels like I’m saying a lie when I say that I will hug my parents for the first time in ten months a mere two months from now. I can’t wait to bike to the beach, to go on runs, to eat copious amounts of salad, and most of all, to see my family and friends. Nonetheless, I feel a bit nervous to leave what seems natural and go back home. It’s a bit ironic; when I came here, for the first few months I wished I were home, where everything was “normal” and manageable. Now, Oman is my “normal”.

I suppose that’s the difficult part of being an exchange student; you are never fully home. Oman and America are both my homes, in different ways. I saw a quote once, which read, “You will never be completely at home again, because part of your heart will always be elsewhere. That is the price you pay for the richness of loving and knowing people in more than one place.” In the first half of the year, when I first saw this, I couldn’t fathom how anyone actually felt this way. I couldn’t imagine being so enamored with another country that it became a second home, but now I do. I left a bit of my heart in Nizwa, and a piece in Wadi Adai, and some in Wahiba Sands.

Let’s go be Bedouins!

Last month, the YES Abroad and NSLI-Y students went on a trip to Wahiba Sands, an area of desert in the interior of Oman. Wahiba Sands is a large expanse of rolling sand dunes, which seemed very foreign in contrast to the more developed Muscat terrain. This area extends to cover over 15,000 square kilometers, with many traditional Bedouin compounds contained within its borders. While there, we went dune-bashing, wadi swimming, and visited a Bedouin house to learn more about this traditional way of life.

In the morning we were all picked up by Mohammed, our bus driver, and brought to AMIDEAST, where we waited for our tour guides. My car’s driver was a man named Ahmed, who was from the area we were going to. After driving for an hour, we stopped for pictures near the village of Sumail, the village where my host mom and her siblings grew up. Our tour guide explained that the forts that dotted the mountains above Sumail were built when tribes tried to drive the inhabitants off of their rightful land.

Once we re-embarked on our drive, it took about two hours until we stopped for pictures at the settlement of Ibra, which was once an influential trading location. Though the village has fallen into disrepair over the years, people still do live there.

Finally, after more than two and a half hours of driving, our road began to change. Gone were the paved roads of Muscat, as we began speeding up and down sand dunes on our way to our final destination, a tourist camp. We stayed there for one night, and went out to the desert the next morning to watch the sunrise.

That morning we managed to ride camels, which thoroughly convinced me that riding across the desert on a camel is indeed my destiny. After this epiphany-inducing activity, it was back to the cars! We started driving up and down sand dunes quickly, as we talked to Ahmed about riding camels. About an hour later, we had arrived at a traditional Bedouin house, where we met a woman who sold Bedouin crafts. She taught us how to make woven bracelets, and showed us some other examples of crafts. We left her house with crafts in our bags, dates and coffee in our stomachs, and smiles on our faces.

Making bracelets proved to be a little complicated, but we quickly got the hang of it! (photo courtesy of Sarah Hale and AMIDEAST)

Yet another hour drive followed before we arrived in a wadi, where we swam until it was finally time to return home. An epic dance party ensued with Ahmed, Quinn, and Hannah as we drove back towards AMIDEAST. Returning to reality was a bit of a crash after the fantastic weekend, but all I know is that I will never forget this incredible experience.